SPINAL INJURY IN REMOTE ENVIRONMENTS

27th April 2014, updated 3rd March 2020 and 18th January 2021

Spinal Injuries are a considerable concern in a remote, industrial or hostile environment given not only the very serious consequences of such an injury but also:

the increased likelihood of spinal injury due to the prevalence of precipitating Mechanisms of Injury which (with the exception of vehicle accidents) are more commonly seen in these environments than in more domestic or urban settings.

the implications and difficulties of extended care and a protracted evacuation from these environments.

The traditional approach of immobilising all suspected spinal injuries with Cervical Collar, Spinal Board, Blocks and Straps has been the Gold Standard for at least 30 years but recently this dogma is being challenged with increasing momentum as erring on the side of caution may not, in fact, be as necessary or beneficial as once thought:

Incidence:

While any casualty with a suspected spinal cord injury (SCI) is typically immobilised, only 0.5%-3% of these casualties are found to have unstable spinal injury or injury to the spinal cord (1, 2)

Spinal cord injuries are much rarer than previously thought, found in only 6.6% of trapped casualties and 4.7% of untrapped casualties yet only present in 0.71% of all vehicle extrications (3).

Of those fractures causing SCI, half involve fractures of the cervical spine, with 37% due to thoracic spine injury and 11% lumbar spine. (4, 5)

Issues:

Spinal Boards are an extrication device and not a stretcher. Due to the risk of pressure sores (6), the casualty should be on one for no more than 30 minutes (possibly extended with padding) (7). Once immobilised a clinician will be unwilling to ‘clear’ a spinal injury until satisfied by not only X-Ray but also CT scanning once in the ED. How long will your casualty be immobilised for whilst waiting for help and during transit?

Spinal boards increase the risk of aspiration on vomit, potentially reduces airway opening and reduce respiratory efficacy by an average of 15% on average (8). These issues challenge the pre-hospital axiom of ‘airway before injury’ “...the possibility that immobilisation may increase mortality and morbidity cannot be excluded.” (9)

Once a collar is fitted, the reduced opening of the casualty’s mouth may make advanced airway management (e.g. intubation or laryngeal airways) more difficult (10, 11). Whilst this may not be within the scope of the person applying the collar, it may impact on the next echelon of care the casualty receives.

To position a casualty on a spinal board requires log-rolling the casualty to 90⁰ on their side. This practice does not limit lateral movement of the casualty and can destabilize clots in the hypotensive casualty. (7)

Cervical Collars are not a panacea and come with their own issues including difficulty in application due to aggressive / combative casualties or bulky clothing, difficulty in correct sizing leading to ineffective immobilisation, potentially forced extension of the spine and increased intracranial pressure.

Cervical collars are proven to raise intercranial pressure (12-14) which is of particular concern given the co-morbity of head injuries with spinal injuries of between 39-58% (15).

Spinal boards do not provide the immobilisation commonly believed (16) or reduce the rate of SCI (17), with Vacuum Mattresses being significantly more effective and without the associate time-bound issues. (18, 19)

Kinematic research shows that the damage done but reasonable movement of a casualty during care is negligible to that of the forces involved in the initial injury which ‘is generally not sufficient to cause further damage’. Furthermore, the alert patient will probably develop a position of comfort with muscle spasm protecting a damaged spine. (20-22)

A 2009 review concluded that the alert, cooperative patient does not require immobilisation even if a clinical decision rule is positive; unless their conscious level deteriorates as muscle spasm is a superior method to an artificial procedure. (23)

Despite the low incidence of Spinal or Spinal Cord Injury and the potential issues with unnecessary and/or prolonged Immobilisation, because of the extreme consequences of a mis-diagnosed or mismanaged casualty as well as the potential litigious costs it is understandable that there is reluctance to apply a more relaxed approach.

Structured guidance would allow the pre-hospital practitioner to make an informed decision which provides best care for the casualty with a suspected spinal Injury whilst negating the need to immobilise those at low risk.

Rules based approaches:

NEXUS

The National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) Low-Risk Criteria was first introduced in 1992. There have been various amendments since then to increase both accuracy and application.

A Cervical Injury can be cleared if:

Canadian Cervical Spine Rule

Where NEXUS attempts to rule out C-Spine Injury based on the confidence of casualty's response to pain and physical assessment, the Canadian Cervical Spine Rules (CSSR) provides clinical criteria based on Risk Factors:

Both NEXUS and CCSR have nearly 100% accuracy in successfully identifying significant spinal injury but have with them their own issues in application and limitations in studied examples (24). The Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC) Guidelines (2013) advocate the use of the NEXUS rules for clearing a spinal injury (7) while the National Institute for Health & Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines (2014) (25) advise clinicians to apply NEXUS based rules to eliminate low-risk factors before assessing the casualty using a CCSR based assessment.

A Remote Protocol for clearing Spinal Injury

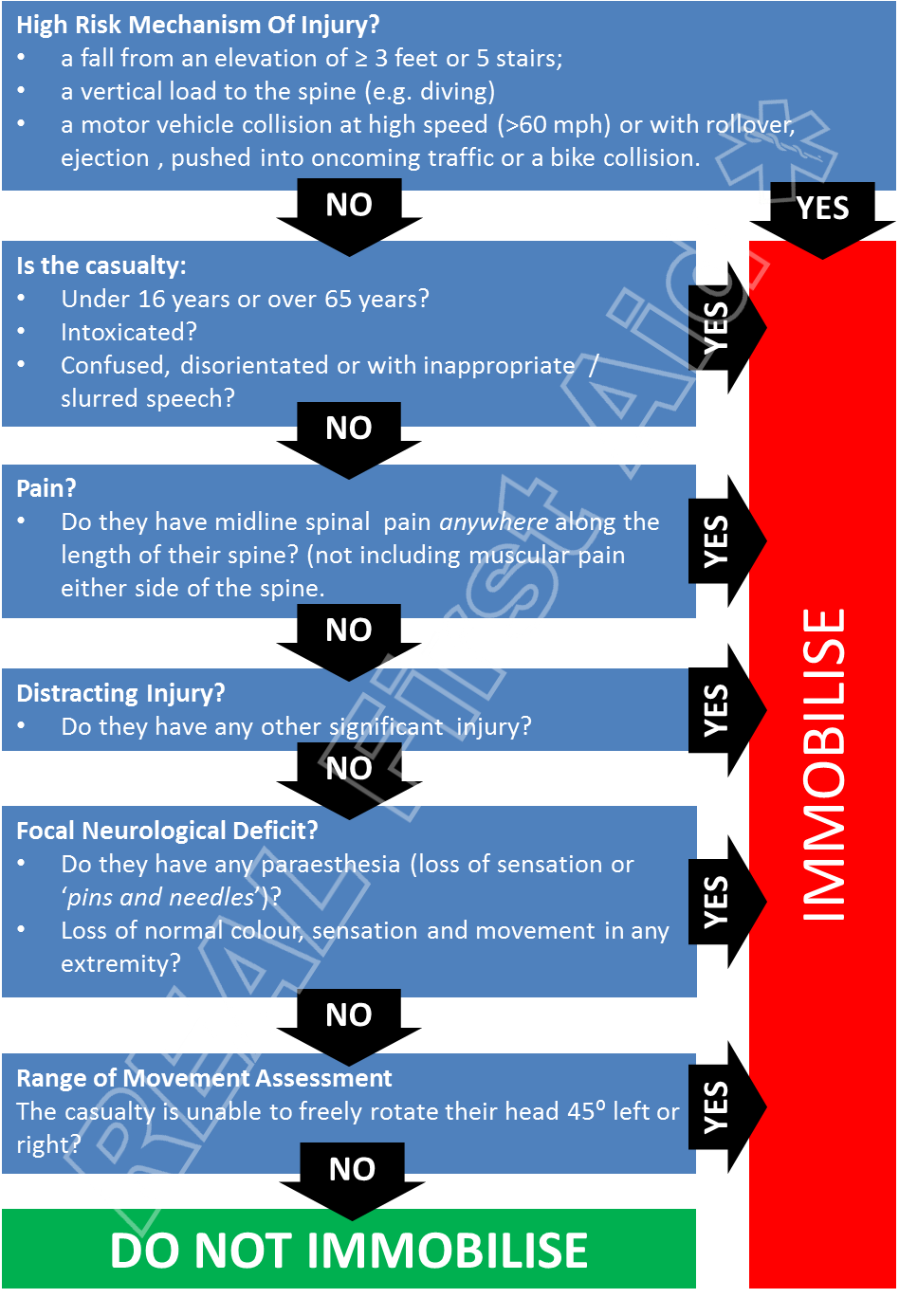

A combination of both systems might afford the pre-hospital carer a framework to make appropriate decisions and provide appropriate care. The following algorithm attempts to simplify and combine both NEXUS and CSSR protocols without losing sensitivity:

To begin with there must be a significant MOI to warrant Immobilisation; both algorithms place significant MOI as the most credible factor in suspected Spinal Injury.

The NEXUS and CCSR rules contradict each other on the validity in age groups either side of 16-65 years. This model errs on the side of caution.

Given the high prevalence of cervical spine injuries alongside thoracic and lumber spine injuries together with recommended immobilisation for all spinal injuries, this model includes pain along the length of the spine, not just the cervical spine.

Range of movement is assessed only after all other factors have been ruled out.

Summery

Conscious casualties should be supported in a comfortable position and manual handling should be limited to assisting the casualty move themselves.

When dealing with an unconscious casualty with a suspected casualty as

a lone-responder, the causality should be placed into the Safe Airway position using the Modified Spinal technique.

as a team or responders, the casualty should be managed on their back, using the log-roll technique to move the casualty when needed.

In both cases, greater emphasis is placed on monitoring the casualty's airway

Related Articles:

Managing Pelvic Injuries in Remote Environments

Back to First Aid articles

References

Cameron P, Bagge B, McNeil J, Finch C, Smith K, Cooper D, et al. (2005) “The trauma registry as a statewide quality improvement tool”. Journal of Trauma. 59:1469-1476.

Burney R, Maio R, Maynard F, Karunas R. (1993) “Incidence, characteristics, and outcomes of spinal cord injury at trauma centers in North America.” Archives of Surgery. 128:596-599

Nutbeam, T., Fenwick, R., Smith, J. et al. A comparison of the demographics, injury patterns and outcome data for patients injured in motor vehicle collisions who are trapped compared to those patients who are not trapped. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 29, 17 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-020-00818-6

Spinal Cord Association. (2009) “Preserving and developing the National Spinal Cord Injury Service: Phase 2 - seeking the evidence”.

Winslow J, Hensberry R, Bozeman W, Hill K, Miller P. (2006) “Risk of thoracolumbar fractures in victims of motor vehicle collisions with cervical spine fractures.” J Trauma. 61:686-687

Ham W et al. (2014) “Pressure Ulcers From Spinal Immobilization in Trauma Patients: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 76(4): 1131 – 41

Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee. (2013) UK Ambulance Service

Totten VY, Sugarman DB. (1999) “Respiratory effects of spinal immobillzatlon.” PrehospitalEmergency Care, 3: 347–52.

Kwan I, Bunn F, Roberts IG. (2009) “Spinal Immobilisation for trauma patients (Review).” Prepared and maintained by The Cochrane Collaboration. Published in The Cochrane Library. Issue 1

Durga P et al. (2014) “Effect of Rigid Cervical Collar on Tracheal Intubation Using Airtraq.” Indian Journal of Anaesthesia. 58(4): 416 – 422

Yuk M, Yeo W, Lee K, Ko J & Park T. (2018) “Cervical collar makes difficult airway: a simulation study using the LEMON criteria”. Clinical and experimental emergency medicine. 5(1). 22–28.

Chestnut RM (1995) “Secondary brain insults after head injury: Clinical perspectives.” New Horizons. 3:366–375, 1995.

Mobbs RJ et al. (2002) “Effect of Cervical Hard Collar on Intracranial Pressure After Head Injury.” ANZ Journal of Surgery. 72(6): 389 – 91. PMID: 12121154

Lemyze M, Palud A, Favory R, et al (2011) “Unintentional strangulation by a cervical collar after attempted suicide by hanging”. Emergency Medicine Journal 2011;28:532.

Budisin B et al. (2016) “Traumatic Brain Injury in Spinal Cord Injury: Frequency and Risk Factors.“ Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 31(4):E33-42.

Wampler DA et al. (2016) “The Long Spine Board Does not Reduce Lateral Motion During Transport – A Randomized Healthy volunteer Crossover Trial”. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 34(4): 717 – 21.

Hauswald M et al. (1998) “Out-of-Hospital Spinal Immobilization: Its Effect on Neurologic Injury.” Academic Emergency Medicine. 5(3): 214 – 219.

Chan D, Goldberg RM, Mason J, Chan L. ( 1996) “Backboard versus mattress splint immobilization: a comparison of symptoms generated.” Journal of Emergency Medicine. 14: 293–8.

Lerner EB, Billittier AJ, Moscati RM. (1998) “The effects of neutral positioning with and without padding on spinal immobilization of healthy subjects.” Prehospital Emergency Care. 2: 112–6.

Hauswald M, Braude D. (2002) “Spinal immobilization in trauma patients: is it really necessary?” Current Opinion in Critical Care. 8:566-570.

Hauswald M, Ong G, Tandberg D, Omar Z. (1998) “Out-of-hospital spinal immobilization: its effect on neurologic injury.” Academy of Emergency Medicine. ;5:214-21

Cowley A. Hague A. Durge N. (2017) “Cervical spine immobilization during extrication of the awake patient a narrative review”. European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 24(3): 158–161

Blackham J, Benger J. (2009) “‘Clearing’ the cervical spine in conscious trauma patients.” Journal of Trauma. 11:93-109)

Andrew Eyre, (2006) “Overview and Comparison of NEXUS and Canadian C-Spine Rules”. American Journal of Clinical Medicine. Volume 3, No. 4.

National Institute for Health & Care Excellence (2014) “Head injury: Triage, assessment, investigation and early management of head injury in children, young people and adults.” Clinical guideline 176