Understanding Chest Pain - Part 1: Heart Attack & Angina

30th May 2018 updated 4th November 2024

What is it?

In this article we will look at heart attack and angina; conditions which are both brought on by a problem with the arteries which feed the heart. The signs and symptoms can be identical but the treatment for each is very different.

| Terminology | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Heart Attack | A colloquialism for a Myocardial Infarction. |

| Myocardial Infarction (MI) | Myo = muscle, Cardio = heart, Infarct = cell death through lack of oxygen. An MI is the death of muscle tissue of the heart; this may cause a Cardiac Arrest or an arrythmia. |

| Cardiac Arrest | The stopping of the heart's normal rhythm. |

| Arrhythmia (AKA Dysrhythmia) | Abnormal electrical activity in the heart producing an abnormal 'heart beat'. |

| Atherosclerosis | A build up of plaque, consisting largely of fats and white blood cells on the inside of the blood vessels. |

| Arteriosclerosis | A build up of calcium deposits resulting in hardening or a reduced elasticity of the blood vessel. |

| Ischemia | Restriction in blood supply. |

| Occlusion | A blockage. |

| Embolism | A blockage of a vessel due to the lodging of a clot or other material which has become detached, travelled in the blood stream and caused an occlusion elsewhere. |

| Thrombus | A blockage at the site of origin of the clot. |

| Hypertension | High blood pressure - continual strain on the vessels walls can lead to weakness and widening of the vessel. This aneurysm is susceptible to rupture. |

| Hypotension | Low blood pressure – typically caused by the heart’s inability to contract and pump blood normally. |

Angina

In simple terms, angina develops due to a restriction in the blood vessels which feed the heart:

Arteriosclerosis is a thickening and hardening or the artery walls which reduces the elasticity of the artery, preventing extra blood volume to pass through during times of increased demand.

This often leads to atherosclerosis which is a build-up of fatty, calcified plaque on the inside of the blood vessel wall, further restricting blood flow.

This reduction in size of the blood vessels reduces blood flow to the heart, especially at times of increased oxygen demand such as stress or exercise. The heart is not completely deprived of oxygen but blood flow is restricted, causing chest pain. This is angina pectoris. (Angina is Latin for ‘strangle’. Pectoris meaning the chest e.g. the pectoral muscles).

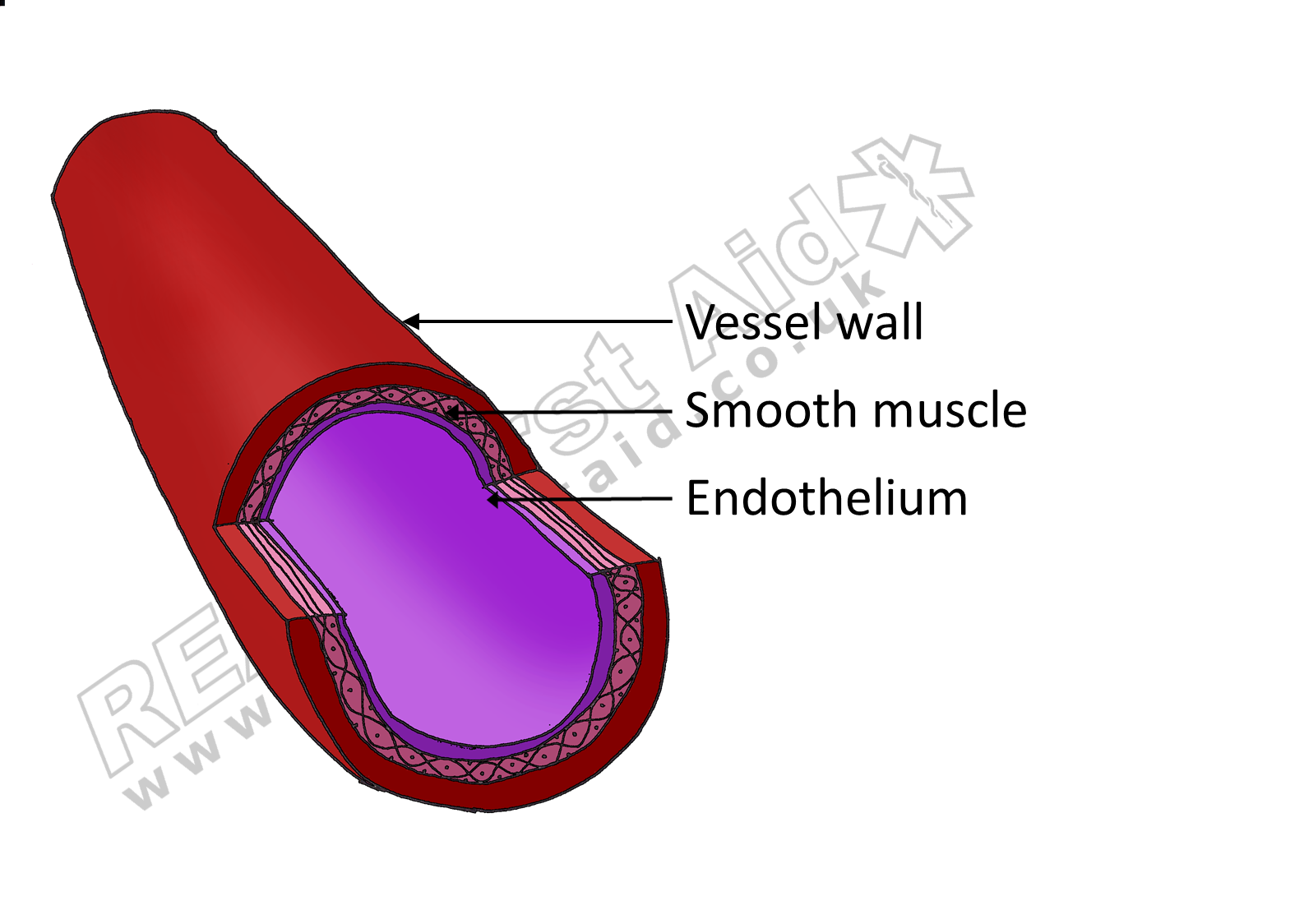

A healthy blood vessel

A sclerotic blood vessel

An embolism

The restriction increases the likelihood of the blood vessel becoming blocked by an embolus.

Continued build up of fatty calcified plaque may also cause the blood vessel to rupture: In a healthy blood vessel the smooth lining of the vessel walls have a layer of epithelial cells which secrete proteins which prevent the formation of clots. The atherosclerotic plaques have no such proteins to prevent clot formation. Furthermore, damage to one of these clots exposes tissue factors and collagen which trigger the clotting mechanism causing a clot to form within the blood vessel.

When a blood vessel becomes completely blocked (an infarction) by a thrombus or embolism the muscle of the heart ( the myocardium) is completely deprived of oxygen causing tissue death. This is a heart attack, correctly called a myocardial infarction or MI.

Formation of a thrombus

A complete thrombus

Thrombus vs embolism?

The terms thrombus and embolism are often used interchangeably and with little distinction between them. A thrumbus is an abnormal clot which forms within a blood vessel i.e. the blockage occurs at the point of origin. An embolism is a blockage which has travelled through the circulatory system to become lodged elsewhere. The embolus is usually a clot from a thrombus but could also be a piece of fatty plaque, an air bubble or even a piece of bone fragment following a fracture.

In summary

A heart attack is caused by a blockage and deprives an area of heart tissue of oxygen.

Angina is caused by a restriction that reduces oxygen to the tissue.

What are the Signs & Symptoms

Let’s get one thing clear: One cannot determine whether a casualty is experiencing an episode of angina or a heart attack based solely on the symptoms. It is often stated in books and on First Aid courses that a heart attack is a ‘stabbing or vice-like central chest pain with a sense of impending doom’ whereas an episode of angina presents a pain that ‘radiates down the left arm or up into the left jaw’.

This is not only a gross simplification, it is wrong.

Both the signs and symptoms of heart attack and angina present as:

The pain experienced during angina or an MI can manifest anywhere in the chest, jaw, back and arms.

A vice-like crushing chest pain or sharp stabbing pain

A pain in the centre of the chest, between the shoulder blades or radiating into either left or right jaw or arm.

An excruciating pain or mild, sometimes mistaken for indigestion.

The casualty may appear pale, sweaty, with difficulty breathing and a look of fear or panic in either case.

Indeed, the term ‘Chest Pain’ is used because it is purposefully vague; the chest is the whole area above the diaphragm, including the sides and back. There are a multitude of adjectives to describe pain. Any pain in the chest should be treated with concern.

In a small retrospective study (1), a cohort of 331 (79.8% male) patients described the chest pain experienced prior to an acute MI as the following:

| Pericardial - directly over the heart, slightly to the left of the sternum | 127 | 38.4% |

| Retrosternal - behind the sternmum | 115 | 34.7% |

| Epigastric - central abdomen | 58 | 17.5% |

| Epigatrium and retrosternum | 3 | 0.9% |

| Back of the chest | 2 | 0.6% |

| No pain but other clinical features | 23 | 6.9% |

| Shoulder, neck and jaw | 75 | 22.7% |

| Chest, shoulder, upper arm and ulnar side of left forearm | 55 | 16.6% |

| Both sides of chest | 42 | 12.7% |

| Only to left side of chest | 11 | 3.3% |

| Interscapular region along with both sides of chest | 10 | 3% |

Pain persisting for >20 minutes was reported by 298 (90%) patients while only 10(3.1%) had pain persisting for <20 minutes.

Given the non-specific nature of the symptoms the casualty describes together with how they appear, the signs and symptoms merely enable to us to recognise a potential heart problem, they do not allow us to differentiate between heart attack and angina. (2) However, severe and prolonged precordial chest pain in a male patient between the age of 41-70 years, with pain radiation to left shoulder, neck and jaw is highly suggestive of AMI.(1)

Gender

With increased age, females report less chest pain and more shortness of breath although no such association was seen with males (3).

Males appear to present with more chest pain but also present with more burning or pricking pain sensation and with more diaphoresis than females (4, 5).

In addition to having a wider variety of possible symptoms (including Symptoms reported more often by females include nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and fear of death (6)), females also present with more symptoms during a given MI than males (7-9).

What are the triggers?

Similarly, both heart attack and angina are triggered by increased oxygen demand on the heart, such as stress and exercise.

What is the treatment?

There are some differences that will quickly and easily enable you to differentiate between a casualty having a heart attack and a casualty with angina through the strategic use of questioning:

1. Angina is a long term medical condition.

The casualty knows they have it and they almost certainly will carry medication for it, typically Glyceryl Trinitrate (GTN). This is usually as a spray or sometimes as a tablet that dissolves under the tongue.

People generally don’t have a history of or frequent heart attacks.

Any casualty who presents with chest pain, sit them down on the floor, up against something to lean on and ask:

“Has this happened before?” and “Do you have any medication?”

If the answers are yes, assume it is angina. If the answers are no. Assume it is a heart attack.

2. A heart attack is life-threatening, Angina is not.

If you suspect the casualty is having a heart attack, call the emergency services and encourage the casualty to chew one 300mg aspirin.

Just in case you missed that, CALL THE EMERGENCY SERVICES.

A heart attack is a medical emergency that can lead to cardiac arrest.

What does aspirin do?

Aspirin does not “thin the blood”, it is an anticoagulant, preventing platelets from sticking together. Aspirin will not treat the heart attack nor will it take away the pain; it is given preemptively in case the casualty goes into cardiac arrest. Blood needs to be in two conditions in order to clot – it needs to be warm and static. If the casualty goes into cardiac arrest the blood is now stationary and warm and clots may develop. If the casualty is lucky enough to be resuscitated and normal circulation resumes, these clots are then deposited around the body increasing the likelihood of another heart attack, a stroke or pulmonary embolism.

The Aspirin should be chewed not swallowed (10, 11). Swallowing an aspirin can take around 26 minutes to produce maximal platelet inhibition; Dispersible aspirin such as Alka-Seltzer can take 16 minutes but chewed aspirin can achieve maximum platelet inhibition in around 14 minutes (12).

If you have oxygen available, remember to check the casualty’s Sp02 before administering. While oxygen seems ideal, high-flow supplemental oxygen can make the problem worse.

Prepare for unconsciousness and CPR.

3. Angina subsides with rest, heart attack does not.

If you suspect the casualty is suffering with angina, sit them down on the floor, against something to lean on and help them administer their medication.

Heart attack is life-threatening, angina is not. There is no need to call the Emergency Services at this stage.

As the casualty rests their pulse will lower, the oxygen demand of the heart will reduce and the pain will subside.

Glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) is a vasodilator that opens the blood vessels allowing more blood flow to the heart.

1 dose (usually two sprays) of GTN spray under the tongue – pain should ease within 5 minutes.

If there is no improvement after 5 minutes, the casualty should administer a further dose.

If there is no improvement after a further 5 minutes, the casualty should administer a third dose. (13, 14)

Because angina should relieve with rest, this is how we differentiate it from a heart attack.

If there is no improvement after a further 5 minutes (15 minutes in total since first administration) assume Heart Attack.

Call 999 and encourage the casualty to chew 300mg aspirin.

Summary

Next Article - Heart Conditions Part 2 - Heart Failure & Aortic Aneurysm - Coming soon...

References

Malik MA, Alam Khan S, Safdar S, Taseer IU. (2013) “Chest Pain as a presenting complaint in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI)”. Pakistan Journal of Medical Science. 29(2):565-568.

Swap CJ, Nagurney JT. (2005) “Value and limitations of chest pain history in the evaluation of patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes”. Journal of the American Medical Association. Nov 23;294(20):2623-9.

Milner KA, Vaccarino V, Arnold AL, Funk M, Goldberg RJ. (2004) “Gender and age differences in chief complaints of acute myocardial infarction (Worcester Heart Attack Study)”. American Journal of Cardiology. 93:606–608.

Joseph NM, Ramamoorthy L, Satheesh S. J (2021) “Atypical manifestations of women presenting with myocardial infarction at tertiary health care center: an analytical study.” Midlife Health. 12:219–224.

Kosuge M, Kimura K, Ishikawa T, et al. (2006) “Differences between men and women in terms of clinical features of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction”. Circulation Journal. 70:222–226

Shin JY, Martin R, Howren MB. West (2009) “Influence of assessment methods on reports of gender differences in AMI symptoms”. Journal of Nursing Research. 31:553–568.

Brush JE Jr, Hajduk AM, Greene EJ, Dreyer RP, Krumholz HM, Chaudhry. (2022) “Sex differences in symptom phenotypes among older patients with acute myocardial infarction”. American Journal of Medicine. 135:342–349.

Brush JE Jr, Krumholz HM, Greene EJ, Dreyer RP. (2020) “Sex differences in symptom phenotypes among patients with acute myocardial infarction.” Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality & Outcomes. 13:0.

Kirchberger I, Heier M, Kuch B, Wende R, Meisinger C. (2011) “Sex differences in patient-reported symptoms associated with myocardial infarction (from the population-based MONICA/KORA myocardial Infarction Registry).” American Journal of Cardiology. 107:1585–1589.

Nordt, S. Clark, R. Castillo, E. Guss, D. (2009) “Comparison of Three Aspirin Formulations” in 2009 Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) Annual Meeting Abstracts. Academic Emergency Medicine, April; vol 16.

Schwertnera, H.A. McGlassona, D. Christopherb, M. Busha, A.C. (2006). “Effects of different aspirin formulations on platelet aggregation times and on plasma salicylate concentrations.” Thrombosis Research. Vol 118,.4, p529–534

Feldman M, Cryer B. (1999) “Aspirin absorption rates and platelet inhibition times with 325-mg buffered aspirin tablets (chewed or swallowed intact) and with buffered aspirin solution.” American Journal of Cardiology. Aug 15;84(4):404-9.

British Cardiac Patients Association (2007) Heart Drugs. P1. http://bcpa.uk/factsheets/Angina.htm

“Using your GTN spray to treat your chest pain” Guy’s And St Thomas NHS Foundation Trust. January 2013. http://www.guysandstthomas.nhs.uk/resources/patient-information/cardiovascular/using-your-GTN-spray-to-treat-your-chest-pain-discomfort.pdf