Pre-Hospital Management of Burns

Part 1: Thermal Burns

Burns can represent one of the most challenging types of trauma; injuries range from mild reddening of the skin through to severe tissue damage with additional complications of infection, hypothermia, electrolyte imbalance, respiratory and cardiac problems and poisoning.

Appropriate management of a burn in a pre-hospital setting requires proper assessment.

Depth of burns

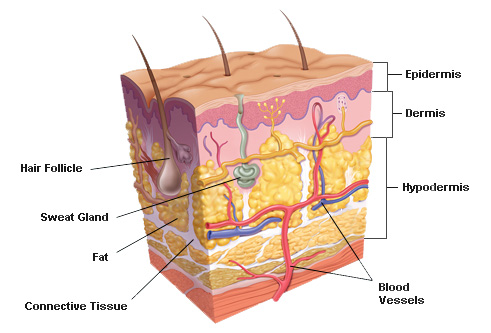

One of the major determining factors in the severity of a burn is understanding how much tissue has been affected and the associated complications with increasingly deeper burns. The depth of the burn is determined by a combination of both the duration and the intensity of exposure.

The longer the exposure and/or the greater intensity the more damage will be done. Initially this may be superficial damage to the outermost layer of skin, the epidermis, appearing as a red, painful wound but without broken skin. As the duration and / or intensity increases, further layers of skin are damaged including the papillary dermis, reticular dermis and eventually through to deeper tissue.

Source: Madhero88 and M.Komorniczak – CC-BY-3.0

Superficial (1st degree)

Source: QuinnHK CC-BY-2.5

Layers involved: Epidermis

Appearance: Red, without blisters

Texture: Dry

Healing time: 5-10 days

Complications: None

Superficial Partial Thickness (2nd degree)

Source: http://auleafoundation.com/miscellaneous/how-to-get-rid-of-blisters/

Layers involved: Superficial dermis

Appearance: Red, with clear blisters

Texture: Moist

Healing time: Less than 2 weeks

Complications: Local infection, fluid loss

Deep Partial Thickness (2nd Degree)

Layers involved: Reticular Dermis

Appearance: Red or white exposed skin

Texture: Initially moist, becoming dry

Healing time: 3-8 weeks

Complications: Local infection,scaring, contractures (tightening of skin)

Full Thickness (3rd Degree)

Source: Craig0927 – Public Domain

Layers involved: Extends through entire dermis

Appearance: Stiff, white / yellow / brown waxy skin

Texture: Leathery

Healing time: Months or incomplete

Complications: systemic infection, scaring, contractures

4th Degree

Source - https://www.tes.com/lessons/biv0S-NCbEId0g/burns

Layers involved:

Extends through entire dermis into underlying fat, muscle and connective tissue

Appearance: Back, charred

Texture: Dry

Healing time: Requires excision

Complications: Amputation, functional impairment, death

Burns are dynamic wounds and the depth can change over the first 72 hours (1). In a prolonged field care environment, monitoring is essential.

As can be see above, as well as the management of pain, you must also consider the risk of local and systemic infection as well as the issue of fluid loss:

Pathophysiology of fluid loss

At temperatures above 44oc, proteins begin to break down causing cell damage (2). This damages reduces the skin’s natural ability to prevent water loss through evaporation, and ability to control body temperature (3) as such large area burns present secondary complications of potential hypothermia. The last thing anyone would suspect with a heat related injury!

Continued cellular breakdown causes cells to leak fluid out of the cells into the intracellular spaces resulting in localised swelling.

Further inflammatory responses causes blood vessels to dilate, become porous and release further fluid into intracellular spaces. (4) It is this shift in fluids which presents life threatening conditions; in burns over 30% body surface area (5) this inflammatory response can lead to sequelae* such as hyponatremia (low sodium levels), hyperkalaemia (high potassium levels) and hypovolaemic shock and eventually death.

*a fabulous word meaning a condition which is the consequence of a previous disease or injury.

Coverage of Burn

Another determinant in the severity of a burn is the coverage of total body surface area (TBSA). To assist with an accurate estimation of TBSA, the Rule of 9s can be used: In the diagram below, areas are broken down into 11 areas that roughly equate to 9% each:

This handy model is far too convenient to be perfect but it provides a relatively quick and easy way to estimate within reasonable margins of accuracy for casualties over 16 years old and up to 80 Kg (6, 7). For Children, different proportions are applied to account for their relatively large head and short limbs in proportion to their trunk.

There is concern over the accuracy of the Rule of 9s for casualties over 80kg, especially obese casualties. A modified rule has been suggested for bariatric casualties (6).

5% body surface area for each arm

20% BSA for each leg

50% for the trunk, and

2% for the head.

Mersey Burns is a useful app available for free on Android and Apple.

Mersey Burns App

Treatment for thermal burns

Thermal burns (flame, contact, scalds) account for the majority of burns presented at A&E in the UK (8). A meta-review of burns treatments conducted in 2010 provides comprehensive guidance to the treatment of thermal burns(9).

Cold running water 2oc-15oc: Water temperatures below 15oc are most effective in relieving pain and promoting wound healing. Water temperature should be limited to 2oc, especially in large are burns, to reduce hypothermia.

Treatment should be maintained for at least 20 minutes for optimum effect. Beyond 20 minutes analgesia should be used for pain relief.

Treatment should be started a soon as possible. There is little benefit in wound healing if cold running water is applied beyond 3 hours of the initial injury.

Burns should be covered with a non-fibrous, non stick dressing. Cling film is ideal in a prehospital setting being relatively sterile and airtight. This reduces the chance of infection and maintains a moist environment to aid wound healing (10-13). The cling film should be applied loosely.

Do not use ice. Ice does not improve pain or wound healing compared to cold running water but can cause tissue damage.

Do not use lotions or cremes. There is no better treatment than cold running water. Antiseptic creams may have marginal benefit on minor burns. The determining factor in wound healing is the clinical treatment at hospital rather than the first aid treatment pre-hospital. Furthermore, oils and cremes present a barrier to the wound which will need to be removed should medical treatment need to be applied in hospital. Neither the casualty nor the nurse will appreciate your efforts when they are scrubbing the wound to remove the product which has been applied.

Hydrogel Dressings

Several hydrogel dressings are available for the treatment of burns. These include “Water Jel”, “Burnshield” and The residue of these water-based dressings are more easily removed that oils or greases. They typically contain a small amount of aloe vera and are designed to increase evaporative cooling. There is little evidence to their efficacy (9, 10) however they are reported to soothe the burn; their effects are attributed to their anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and antifungal properties. Hydrogel dressings have two important benefits is an industrial or remote environment.

As a substitute when 20 minutes of clean, running water is not available.

Hydrogel face dressings are more tolerable than 20 minutes of running water to a facial injury.

Because of the evaporative cooling, hydrogel dressings should be limited to burns of >20% TBSA in adults or >10% TBSA in children. (9)

Blisters – to pop or not to pop?

Blisters serve a function; fluid leaking from damaged cells is retained under the epidermis. This creates a protective environment for wound healing. Over time the fluid is reabsorbed or the blister will burst in due course. The argument for not popping blisters is that it interrupts the natural healing mechanism and increases the risk of infection.

The argument for popping blisters is that the increased fluid pressure within the blister can increase pain and reduce joint mobility.

Our rational is this: If it is going to pop, pop it. If it is not going to pop, leave it. For example, a blister the palm of a hand or heal of a foot is going to pop because these are high-wear areas of the body, subject to rubbing and impact. It is safe to pop the blister in a controlled, sterile manner and dress it appropriately than let it pop naturally, within a dirty sock for example, where the risk of infection is greater. If it is not likely to pop due to impact or damage, leave it. (14)

Hospitalization

The World Health Organization (15) provides the following guidance for determining hospital referral for the treatment and management of serious burns.

Partial thickness burns >15% ( >10% children)

Any full thickness burn

Any elderly or infant burn casualty

Any burn to the face, hands, feet or genitalia

Circumferential burns

Inhalation injury

Any significant pre-burn illness e.g. diabetes

Because of the complexities associated with the assessment and management of burns, we would advocate referral to hospital if there is any concern.

Next Article: Burns Part 2: Chemical, Electrical and Cryogenic Burns

References:

Green M, Holloway A, Heimbach DM(1988) “Laser Doppler Monitoring of Microcirculatory Changes in Acute Burn Wounds”. Journal of Burn Care & Rehabilitation 9(1):57-62

Marx, John (2010). "Chapter 60: Thermal Burns". Rosen's emergency medicine : concepts and clinical practice (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier.

Tintinalli, Judith E. (2010). Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies. pp. 1374–1386.

Brunicardi, Charles (2010). "Chapter 8: Burns". Schwartz's principles of surgery (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division.

Rojas Y, Finnerty CC, Radhakrishnan RS, Herndon DN (December 2012). "Burns: an update on current pharmacotherapy". Expert Opinion Pharmacotherapy. 13 (17): 2485–94

Wachtel TL, Berry CC, et al. (March 2000). "The inter-rater reliability of estimating the size of burns from various burn area chart drawings". Burns. 26 (2): 156–170.

Wachtel TL, Berry CC, et al. (March 2000). "The inter-rater reliability of estimating the size of burns from various burn area chart drawings". Burns. 26 (2): 156–170.

Stylianou N, Buchan I, Dunn KW.(2015) A review of the international Burn Injury Database (iBID) for England and Wales: descriptive analysis of burn injuries 2003–2011 BMJ Open 2015;5:e006184. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006184

Cuttle L & Kimble RM(2010) “First aid treatment of burn injuries”. Wound Practice and Research. 18(1): 6-13

Tiong, W.H. (2012) “Emergency Burn Care in Practice: From first contact to operating theatre” Burns – Prevention, Causes and Treatment. McLaughlin ES, Paterson AO (Ed.)

Hettiaratchy, S. and Dziewulski, P. (2004a) ABC of burns: introduction. British Medical Journal 328(7452), 1366-1368

Settle, J.A.D. (Ed.) (1996) Principles and practice of burns management. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

NZGG (2007) Management of burns and scalds in primary care. New Zealand Guidelines Group. www.health.govt.nz

Shaw, J. & Dibble, C. (2006) "Management of burns blisters". Emergency Medicine Journal. 23(8), 648–649.

World Health Organization (2007) “Management of Burns” WHO Surgical Care at the District Hospital. WHO.