Casualty Positioning

26th December 2014. updates 21st January 2020

Once you've treated the injury or illness you are not quite out of the woods until further help arrives. In that time, correct positioning of the casualty can aid recovery in the same way that poor positioning can very easily aggrevate the injury or exacerbate the condition. Here are a few positions to consider.

Safe Airway Position

Without airway management equipment or techniques unconscious casualties will die on their back. We can open their airway with a simple head tilt but this does not prevent fluids (blood or saliva) draining down or coming up (vomit or blood) and entering the airway.

Any unconscious casualty (even with a suspected spinal injury) should be positioned onto their side because, quite simply, if you don't have an airway, you don't have a casualty.

Regardless of whether you call it the Safe Airway Position, Recovery Position, Drainage Position, Left lateral Recumbent or Three-Quarter Prone, we're going to flip them over.

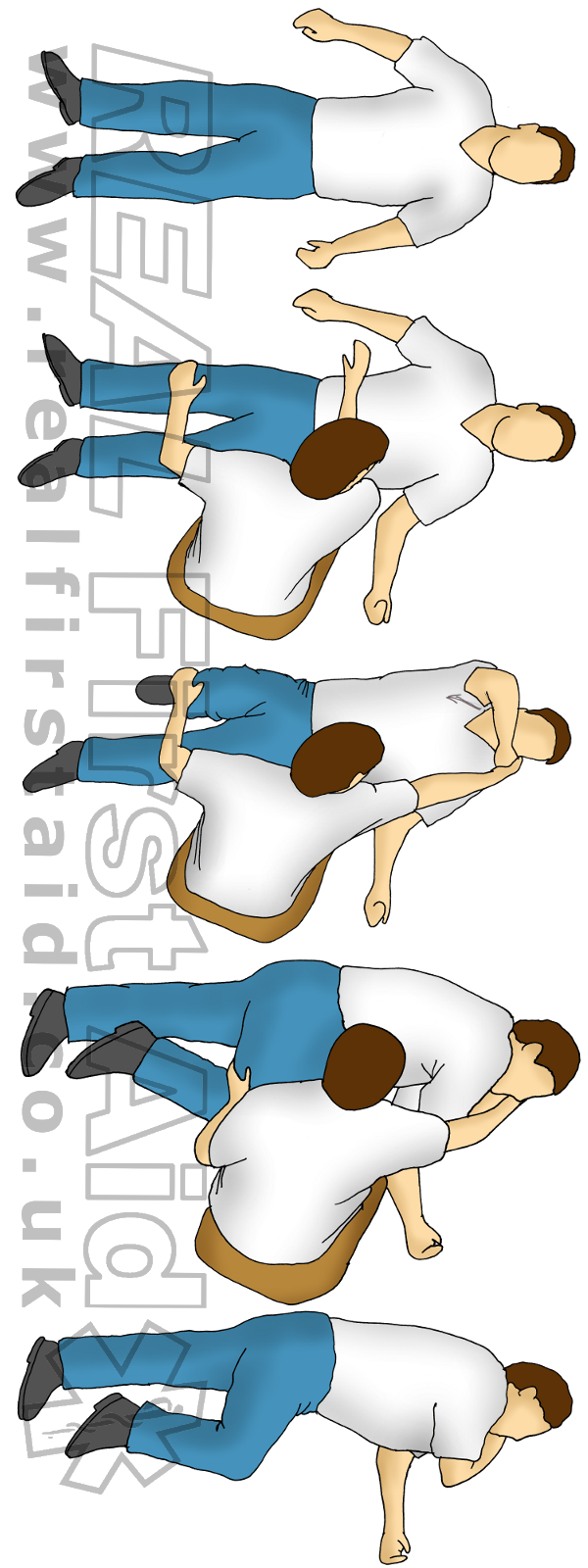

How to do it

- Remove the casualty’s glasses, if present.

- Kneel beside the casualty and make sure that both their legs are straight.

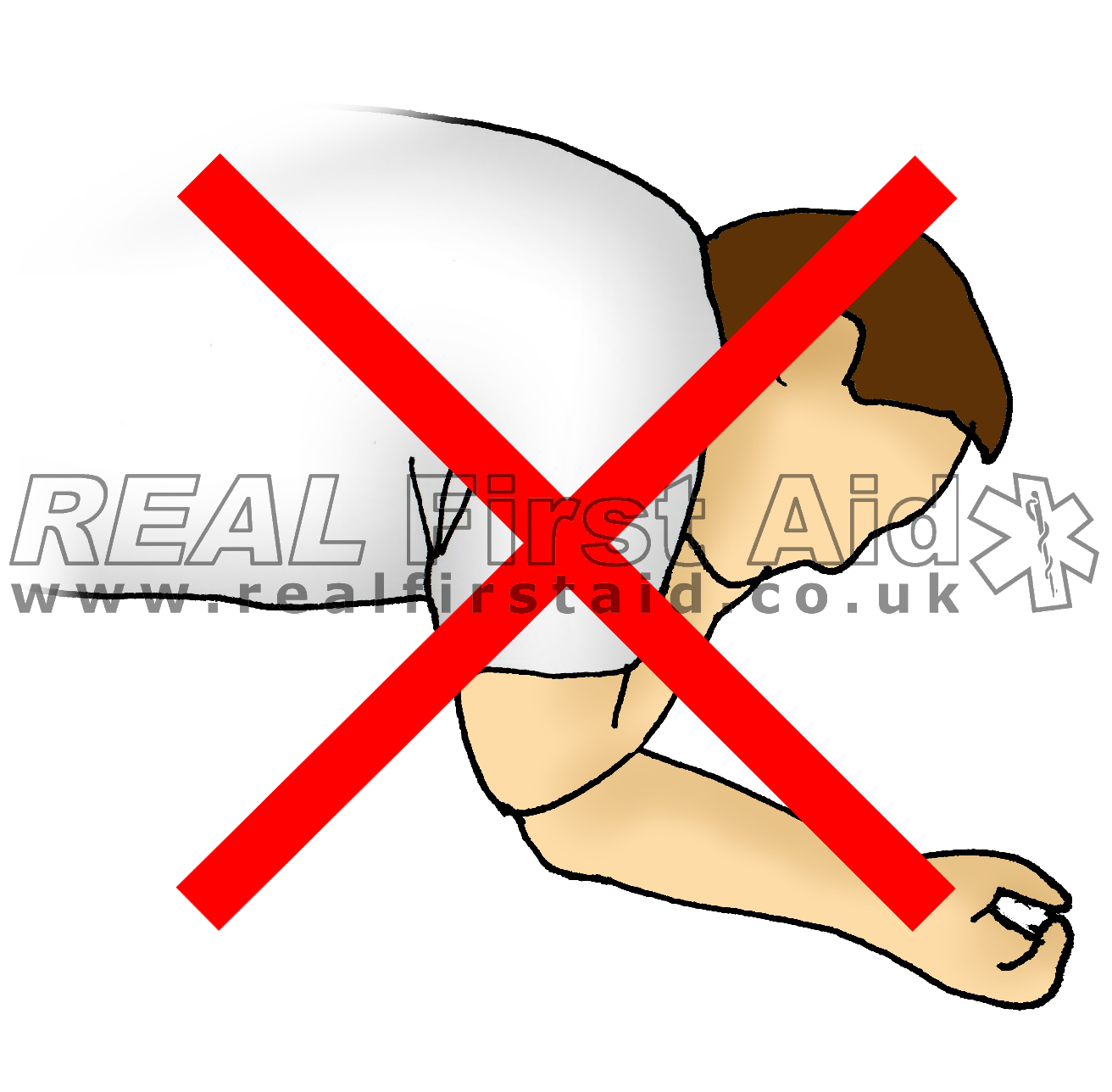

- Place the arm nearest to you out to you side – DO NOT place the shoulder and elbow at right angles. This is unnecessarily painful for people with limited range of movement and places pressure on the lower arm.

- Bring the far arm across the chest, and hold the back of the hand against the casualty’s cheek nearest to you.

- With your other hand, grasp the far leg just above the knee and pull it up, keeping the foot on the ground.

- Keeping their hand pressed against their cheek, pull on the far leg to roll the casualty towards you on to their side.

- Adjust the upper leg so that both the hip and knee are bent at right angles.

- Tilt the head back to make sure that the airway remains open.

- If necessary, adjust the hand under the cheek to keep the head tilted and facing downwards to allow fluids to drain from the mouth.

- Check breathing regularly.

- If the casualty has to be kept in the recovery position for more than 30 min turn him to the opposite side to releive the pressure on the lower arm.

Left of Right?

The Safe Airway Position is often called Left lateral Recumbent, especially in the US. There is sometimes milage in positioning the casualty on their left; the most cited reason - and most plausible - is significant for women in the later stages of pregnancy when positioning the casualty on their right will apply pressure from the foetus onto the inferior vena cava (one of the two large vessels which return deoxygenated blood to the heart) impeding circulation.

Other reasons include:

The stomach curves to the left, so vomit would have an extra curve to overcome

The stomach curves to left, so contents won't be pushing against the sphincter.

In the ambulance, the attendant can observe them better facing toward him.

Improved ventilation given the right lung is slightly larger than the left and left main stem bronchus being at an angle

There is no real evidence for any of these justifications so it would seem that many of the reasons given are - as is often the way in First Aid - largely historical clichés perpetuated because it is really easy to teach people what you have been taught rather than actually understanding what you are teaching.

In fact, positioning on the left can have adverse effects for some conditions, such as Congestive Heart Failure (1) or increase absorption of ingested poisons (2).

Let’s be pragmatic.

Depending on the position your casualty is already found in and obstacles around them you may not have the luxury of this choice. Practice positioning your casualties on either left or right and position them appropriately to

Maximize drainage

without aggravating injuries.

The exception is chest injuries where we roll casualties with chest injuries onto the injured side to protect the unaffected lung.

Safe Airway Position Right

Safe Airway Position Left

Lying Down

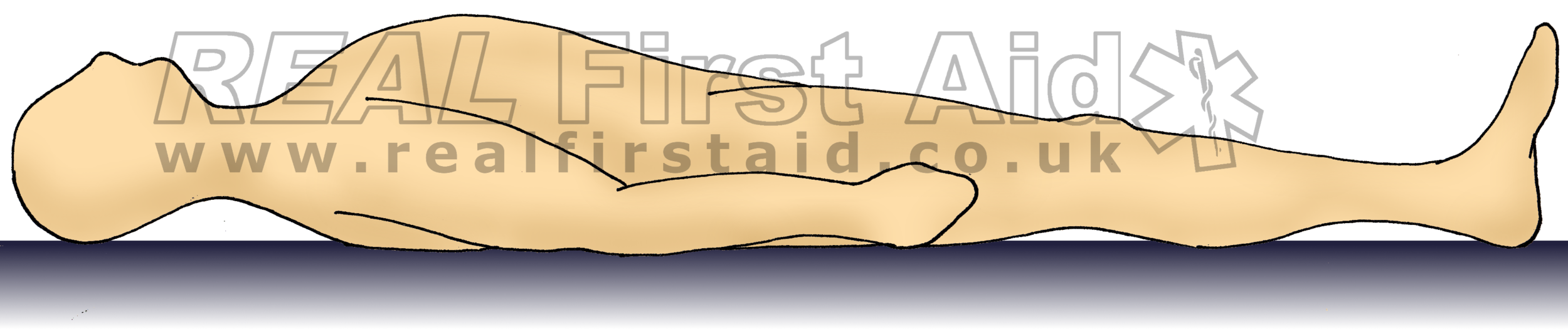

Recumbent

Supine

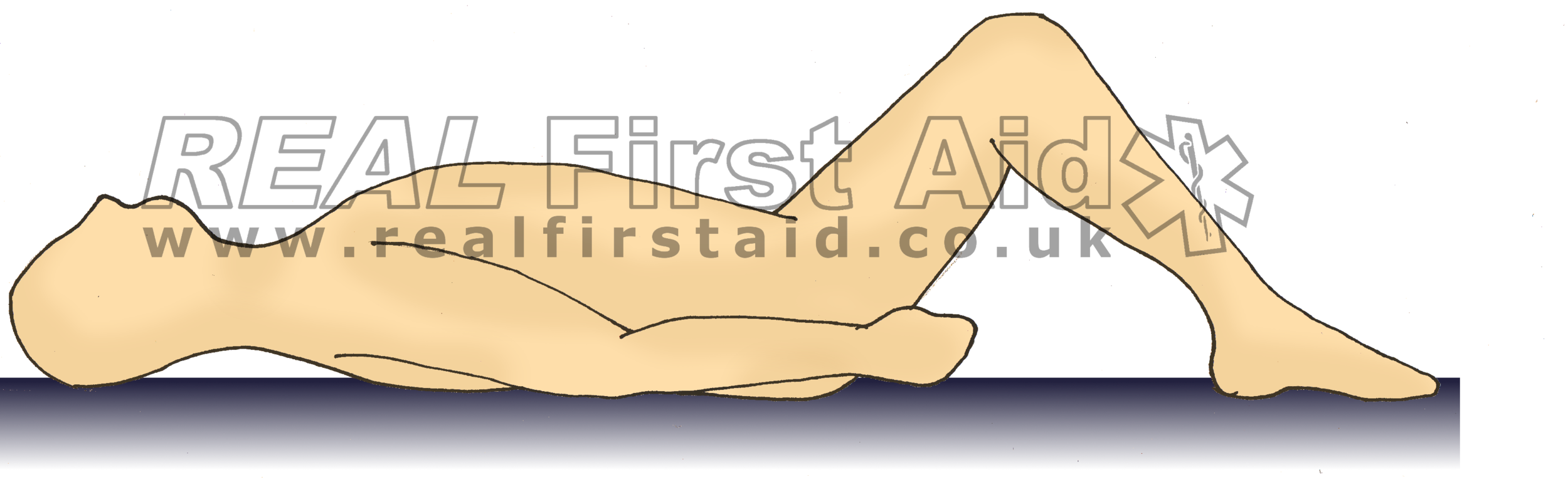

Supine - Knees Bent

Trendelenburg

Inclined

If the causality is alert or we are able to manage their airway with suction and airway adjuncts, it is sometimes beneficial for the casualty to remain on their back.

Recumbent is a posh word for simply lying down with their head supported by a pillow and is the most common and appropriate position for someone who simply needs rest. A slight modification for this would be to remove the pillow which would be appropriate for someone with a suspected spinal injury. This position is now called Supine. Neither of these positions are recommended for head injury (where the priority is to reduce intracranial pressure) or for casualties with breathing problems or chest pain.

Sometimes a tilt can help; most ambulance trolleys will have this option but in the outdoors we have hills and slopes we can utilise. With the legs elevated the Trendelenburg position can improve venous drainage from lower limbs and improve blood supply to the head but with pressure on the diaphragm from below, respiration can be reduced. Inclining the whole body downhill can reduce intracranial pressure and without pressure on the diaphragm, easy respiration.

In reality…

The conscious casualty will assume the most comfortable position.

It is a nonsensical to teach individuals the best position for a conscious casualty.

A casualty with chest pain or difficulty breathing will probably not want to lie flat - they often prefer to sit up, slightly inclined so we don’t need to tell them to do this.

A casualty with abdominal pain may tend to go foetal - so don’t force them to lay flat because that is what you did on your course or read in a book.

In reality, most conscious casualties with these conditions won't let you lay them flat.

Supporting under the knees may relieve pain from pelvic injuries - this is subjective so offer it, but don't force it.

For years we have been told that the casualty who is in shock needs to lie down with their legs elevated because this will drain blood from the legs into the core to:

Improve cardiac output

Improve systemic vascular resistance

Improved mean arterial pressure

Improved systolic blood pressure

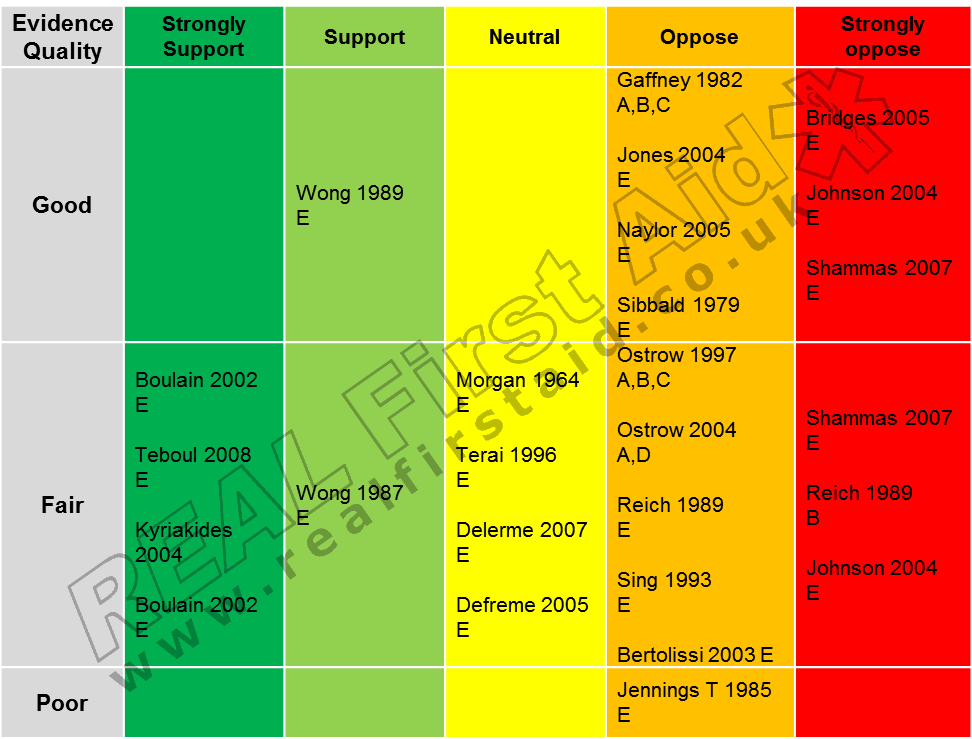

There is limited evidence that elevating the legs may provide a transient (<7 min) improvement in heart rate, mean arterial pressure, cardiac index, or stroke volume; (3-5) for those with no evidence of trauma. However, one study (6) published in 2020, has reported adverse effects due to elevating the legs.

There is no evidence that applies to a hypovolaemic casualty who is already compensating. If you think about it, you know there is no available blood in the legs because the casualty is cold and pale - they are already shunting any available blood to the core by vasoconstriction.

ERC 2020 draft guidelines state:

• Place individuals with shock into the supine (lying-on-back) position

• Where there is no evidence of trauma first aid providers might consider the use of passive leg raising as a temporizing measure while awaiting more advanced emergency medical care.

”Because improvement with Passive Leg Raising is brief and its clinical significance uncertain, it is not recommended as a routine procedure, although it may be appropriate in some first aid settings.”

After Epstein (2010) (7) and Schunder-Tatzber (2010) (8) and

A = Improved Cardiac Output

B = Improved Mean Arterial Pressure

C = Improved Systemic Vascular Resistance

D = Improved Systolic Blood Pressure

E = Other benefits

Anaphylaxis

Several awarding bodies still teach this for the treatment of hypovolemic shock as well as the treatment of anaphylactic shock. This position may be helpful for the anaphylactic casualty with low blood pressure but given 80% of cases present with skin rashes and 70% with difficulty breathing compared to the 10-45% who present with low blood pressure (9) elevating the legs could be the absolute worst thing you can do for them. For the conscious casualty, they will adopt a comfortable position, probably the W Position or Semi Recumbent (10,11). Anyone unconscious is placed into the Safe Airway Position if airway management equipment and techniques are not available.

Conclusions

Don't just leave them as you found them for fear of causing injury and neither flip them into a textbook position just because you were told to once.

Prioritise the airway - even with a spinal injury - a casualty without a clear and open airway will not last long.

If the casualty is conscious allow them to adopt the most comfortable position for them; they will know what relieves pain or eases breathing much better than you and they will not appreciate being forced into an uncomfortable position just because it 'looks right'.

Be pragmatic: Do the best you can based on the position they are found in and the obstacles around them with as little movement as possible to avoid aggravating injuries. More often than not the Real World is not Text Book.

References

Palermo P, Cattadori G, Bussotti M, Apostolo A, Contini M, Agostoni P. (2005) "Lateral decubitus position generates discomfort and worsens lung function in chronic heart failure." Chest. Sep;128(3):1511-6.

Vance MV, Selden BS, Clark RF. (1992) "Optimal patient position for transport and initial management of toxic ingestions”. Annals of Emergency Medicine. Mar;21(3):243-6.

Wong DH, O'Connor D, Tremper KK, et al. (1989) “Changes in cardiac output after acute blood loss and position change in man”. Critical Care Medicine. Oct;17(10):979-983

Jabot J, Teboul JL, Richard C. et al. (2009) “Passive leg raising for predicting fluid responsiveness: Importance of the postural change”. Intensive Care Medicine. 35:85-90

Gaffney FA, Bastian BC, Thal ER, Atkins JM, Blomqvist CG. (1982) “Passive leg raising does not produce a significant or sustained autotransfusion effect”. Journal of Trauma. 22(3):190–193.

Toppen W, Aquije Montoya E, Ong S, et al. (2020) “Passive Leg Raise: Feasibility and Safety of the Maneuver in Patients With Undifferentiated Shock”. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 35(10):1123-1128.

Epstein JL. (2010) “What is the optimal position for a person in shock? Does elevating the legs improve outcome?” Worksheet for Evidence-Based Review of Science for Emergency Cardiac Care. http://circ.ahajournals.org/site/C2010/FA-1601A.pdf Accessed 8th November 2014

Shunder-Tatzber S. (2010) “What is the optimal position for a person in shock? Does elevating the legs improve outcome?” Worksheet for Evidence-Based Review of Science for Emergency Cardiac Care. http://circ.ahajournals.org/site/C2010/FA-1601C.pdf Accessed 8th November 2015

Simons FE. (2009). "Anaphylaxis: Recent advances in assessment and treatment". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 124 (4): 625–36; quiz 637–8.

Pumphrey RS. (2003) “Fatal posture in anaphylactic shock”. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 112(2):451-2.

Soar J, Deakin CD, Nolan JP, Abbas G, Alfonzo A, Handley AJ, et al. (2005) “European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2005 Section 7. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances.” Resuscitation. 67 Suppl 1:S135-70.