Managing musculoskeletal injuries.

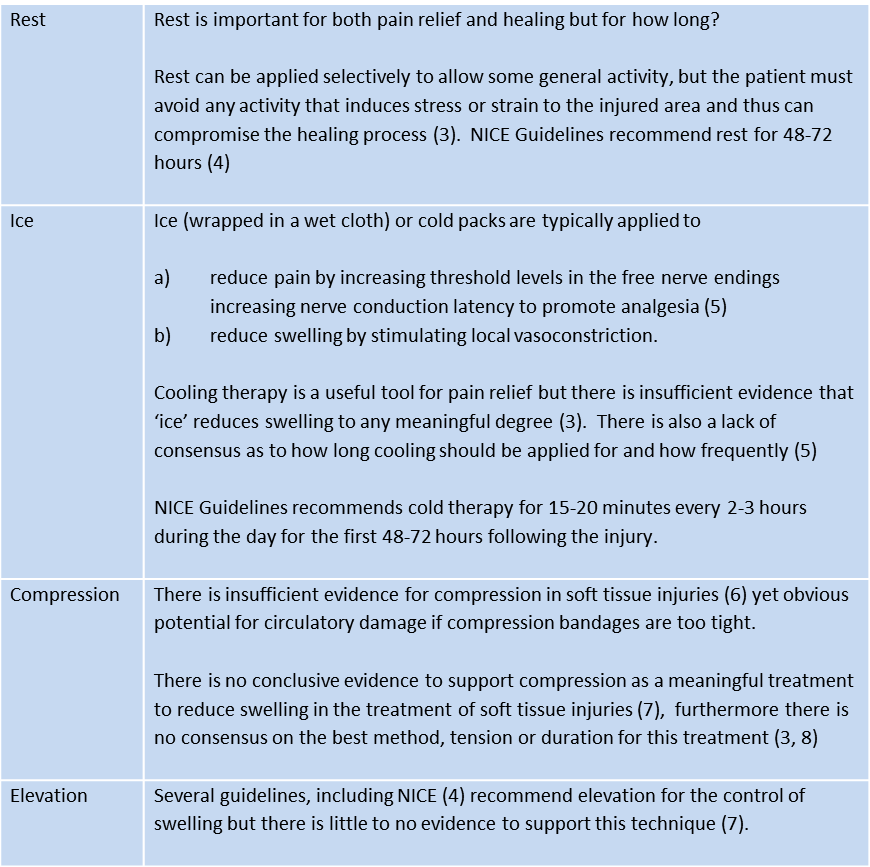

The mnemonic RICE (Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation) has been in use since 1978 when first documented by Dr Gabe Mirkin and Marshall Hoffman in their book “The Sports Medicine Book” (1) and it was quickly and widely accepted as a simple, easy to apply, method for dealing with soft tissue injuries. After nearly 30 years of research there is very little evidence to support this protocol but it is still taught and administered.(2)

The merit of teaching RICE is that it is easy and we apply it to all injuries, fractures, sprains, strains and dislocations. Rather than having to worry about diagnosing the injury and treating that injury in a particular way, we can treat all injuries in the same way. Easy? Or just lazy?

Add to the confusion that there are many variations to RICE, which one do you subscribe to?

PRICE – Protection, Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation (4)

HI-RICE – Hydration, Ibuprofen, Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation (9)

PRICES – Protection, Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation, and Support (10)

PRINCE – Protection, Rest, Ice, NSAIDs, Compression, and Elevation (11)

RICER – Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation, and Referral (12)

POLICE – Protection, Optimal Loading, Ice, Compression, and Elevation (13)

The REAL First Aid approach to musculoskeletal injuries

The approach has three distinct phases that are taught and applied in a simple model.

1. Assessment

2. Pain Management

3. Treatment

1. Assessment

Whilst we may not be able to diagnose a sprained wrist from a fracture we can – and should – assess the injury. Doing so:

a) will provide a benchmark for reassessment of both pain and damage to determine improvement or deterioration over time

b) might reveal damage to important underlying structures.

CSM Assessment

A physical examination may reveal more sinister damage to blood vessels or nerves.

The assessment of Circulation, Sensation and Movement (CSM) will be done before the injury is treated and after. If there is a loss of one or more of these features after treatment, it could be a result of your treatment. If this is the case, undo all of those bandages and reassess.

These features will also be assessed regularly along with the casualty’s vital signs until further help arrives. If one of these features is lost at some point, note the time and pass that information on in your handover.

Further Reading - The Art of Questioning - SAMPLE

Further Reading - The Art of Questioning - PQRST

2. Pain Management

Pain in itself is not life threatening but pain can cause physiological changes in blood pressure, breathing and pulse. This is interesting but the main reason to manage a casualty’s pain, is to make your life and theirs more bearable.

A pain-free casualty will be

more compliant

more willing to engage in their own treatment

less dependent on others

easier to move and transport

more willing to accept potentially painful procedures such as examination or wound cleaning, for example.

Better rested with less disturbed sleep, less stressed and generally a nicer person to be around. This is especially important in remote areas when living in small groups or teams and in confined areas!

There are two methods we can employ to help reduce pain; medicated and non-medicated. For more information, go to Pain Management.

3. Treatment

After pain has been managed, our treatment is limited to reducing movement. Movement aggravates pain and inhibits healing. How involved our treatment is will depend on several factors.

Are they able to support the injury themselves?

How much pain is the casualty in?

Do we have to move the casualty?

How long will we be with the casualty?

For example, a casualty who has fallen onto an outstretched hand, with only a mild amount of pain, close to definitive care, who has full range of movement and CSM, who is not going to be moved may not require any additional support other than ‘nursing’ their arm whilst cold therapy or pain relief is administered.

A casualty with an obvious fracture dislocation, whose ankle is clearly displaced, in considerable pain and is far from help will clearly require immobilisation.

This requires the care giver to make an informed decision. Immobilisation is time consuming, always more difficult in reality than in the classroom and is likely to cause pain whilst being applied to the casualty. As such a more pragmatic approach is promoted of “doing as little as is needed, not as much as can be done”.

The options available to us are:

Summary

Rather than promoting RICE as a panacea for all injuries a more considered, pragmatic approach is required. This three stage model allows the First Aider to assess, make informed decisions and treat the casualty appropriately and to the best of their ability.

References

Mirkin G. and Hoffman M. (1978) The Sports Medicine Book. Little Brown and Co. p.94

van den Bekeron, M.P.J., Struijs, et al ( 2012 ) What Is the Evidence for Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation Therapy in the Treatment of Ankle Sprains in Adults?. Journal of Athletic Training. 47( 4), 435- 443.

Kerr KM, Daley L, Booth L, Stark J. (1998) “PRICE guidelines: guidelines for the management of soft tissue (musculoskeletal) injury with protection, rest, ice, compression, elevation (PRICE) during the first 72 hours (ACPSM)”. Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sports and Exercise Medicine. 6:10–11.

National institute for Clinical and Healthcare Excellence (2016). "Sprains and strains". Clinical knowledge Summaries. http://cks.nice.org.uk/sprains-and-strains#!scenario Accessed 28th July 2016

MacAuley D. (2001) Do textbooks agree on their advice on ice? Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 2001;11(2):67-72.

Hansrani, V., Khanbhai, et al ( 2015 ) The role of compression in the management of soft tissue ankle injuries: a systematic review. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology. 25( 6), 987- 995.

van den Bekeron, M.P.J., Struijs, et al ( 2012 ) What Is the Evidence for Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation Therapy in the Treatment of Ankle Sprains in Adults?. Journal of athletic training. 47( 4), 435- 443.

Airaksinen O, Kolari PJ, Miettinen H. Elastic bandages and intermittent pneumatic compression for treatment of acute ankle sprains. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabillitation. 1990;71(6):380–393.

Tilton B. (2003) “Trekker’s handbook – Strategies to Enhance your Journey”. Mountaineers Books, Seattle, Washington. p94

Kannus P. (2000) Immobilization or early mobilization after an acute soft-tissue injury? The Physician and Sportsmedicine. 2000 Mar;28(3):55-63.

Blesi M, Wise BA, Kelley-Arney C. (2011) Medical Assisting Administrative and Clinical Competencies. Cengage Learning. p1241

Llewelyn H, Ang HA, Lewis K, Al-Abdullah A. (2014) Oxford Handbook of Clinical Diagnosis. Oxford University Press. p447.

Starkey C. (2013) Therapeutic Modalities. FA Davies. p14.

Braund, R., Haxby Abbot and J. ( 2007 ) Analgesic recommendations when treating musculoskeletal sprains and strains. New Zealand Journal of Physiotherapy. 35( 2), 54- 60.

Orchard, J.W., Best, et al ( 2008 ) The early management of muscle strains in the elite athlete: best practice in a world with a limited evidence basis. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 42( 3), 158- 159.

Carter, D. and Amblum-Almer and J. ( 2015 ) Analgesia for people with acute ankle sprain. Emergency Nurse. 23( 1), 24- 31

Mehlisch DR, Aspley S, Daniels SE, Southerden KA, Christensen KS. (2010) "A single-tablet fixed-dose combination of racemic ibuprofen/paracetamol in the management of moderate to severe postoperative dental pain in adult and adolescent patients: a multicenter, two-stage, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, factorial study.". Clinical Therapeutics. 2010 Jun 32 (6): 1033-4